This wasn’t the first such “event” actually — the first came in mid-October during a brutal heat wave, while climbing the steep hill to my home. The pain was an annoying pressure in the center of my chest, as if being stood upon with a heavy boot. I figured all I had to do was get home, sit down, drink some water, and all would be well. And that’s exactly how it turned out. At the time I could not imagine it as a cardiac issue, but perhaps something to do with my esophagus. I simply did not fit the profile.

Anyway, the second time was about a week later. I was in bed at 3 AM, not exerting myself at all, just trying to go to sleep. Changing my position had no effect on the chest pain, and I decided to get up for a wee and a drink of water, as I often do. Half an hour later, my discomfort subsided, but I made a mental note that this should be looked into. Whether these first two events were angina or myocardial infarctions will never be known — the sensations are similar, though MIs can be far more severe.

The third time was a week after, on the morning of my birthday. It was about 7 AM, and I wanted to go back to sleep — except the chest pain wouldn’t allow that. So I rang up the Kaiser advice nurse, who simply told me to go to the ER. By the time I was dressed and ready to go, the pain had gone away. So I rode the bus and walked myself to Kaiser’s ER, including a long block uphill at the end (don’t try this at home, folks).

Jonah in the Whale

I had no idea of what was to come — I imagined they’d let me go after a few hours, so I’d still make it to my birthday lunch with a friend at Pizzeria Delfina. Virtually every previous encounter with Kaiser had been that anticlimactic. But soon after I was ushered to my bed and given drugs and a blood test, a cardiologist informed me that the test showed I’d had a heart attack, so I needed further examination. As if on cue my chest pain returned, which prompted a sense of urgency among the staff. While I was being rolled out of the ER, the cardiologist said, “You’re having a heart attack, Mr. Mathias.” At last reality was sinking in, yet it remained somehow dreamlike.

The rest of the day was a blur of tests and scanning procedures, including coronary catheterization, X-rays, CT, and ultrasound. Under the circumstances it was all I could do to follow the barrage of explanations and relax as much as possible. I can well imagine how others would be in a state of fight-or-flight distress in this situation, especially as I’ve never regarded Western medicine with much confidence. I still have a healthy skepticism of the medical establishment, but it’s more nuanced now.

By the end of the day I had my own room in the ICU, IVs in both arms, and EKG sensors stuck on my chest for constant monitoring. In addition, though it was likely superfluous, a pair of inflatable sleeves squeezed my calves to reduce edema. All this equipment made even the simplest action (like getting out of bed to use the loo) a real production number, esp. under the influence of new drugs.

There was one distressing setback partly due to the blood thinners: the pressure cuff on my right wrist meant to close the catheter puncture was on too tight for too long, and my hand ballooned with massive bruising (hematoma) to my right arm. Luckily there was no lasting damage, and really no one was to blame. And as I’ve said about travel adventures, better to get the bad luck out of the way early. Spoiler Alert: After this things did go according to plan, for the most part.

Living Hospital Style

Once I was stable enough to graduate from the ICU, I was moved to a private room on the fifth floor ward, which specialized in patients awaiting cardiac procedures. In hindsight this was the most comfortable part of my two-week stay, though in hospital true comfort always remains just out of reach. The doctors (by now I had a team, who took turns) explained that as I had three coronary arteries 60-70% blocked, a bypass operation was my best bet for my long term health as compared to stents. The fact that I was in good shape going in helped a lot. The only thing delaying the operation was an anticoagulant that was given me in the ER that needed to clear my system.

Though I would have preferred spending that week at home, the silver lining was easy to see. This gave me time to prepare and get accustomed to the rigors of hospital life, which would soon ramp up to the next level. My friends Beverly and Michael were extremely helpful, bringing me essentials from home (clothes, toiletries, tablet, etc.) that I would need for the post-op phase. Though I didn’t want to believe it at first, clearly I had to line up an assisted-living facility as a safe, supervised environment in which to get stronger before returning to my flat (which also needed a deep cleaning).

Despite my dramatic entrance as someone who had just had a heart attack, I was still in better condition than most of the cardiac patients, esp. those who were older and had other health issues. Being mobile and restless, I was allowed to walk the halls for exercise in my gown and grippy socks, schlepping my trusty IV rack that I dubbed “the Christmas tree”.

Inevitably I observed how much Kaiser had changed since I worked there in the late ‘80s as a library assistant — not just in terms of the hospital being larger, but the huge technological advances. As Grandpa Simpson might have put it, “Back in my day, we carried pagers and sent faxes.” Looking out the windows, I saw the road where my parents regularly drove up to Sears (“Where America Shops”). Not to get nostalgic, but my memory of old San Francisco, i.e., in the 20th Century, was that people lived more in public, collectively and individually. If you see archival photos and films of cities as they once were, notice how alive the streets appear. In today’s cities, people and things may be transported here and there more efficiently, but the bustling vitality seems to have drained away. Why even have cities anymore?

For me some aspects of hospital life stood out as a surprise, like the never-ending parade of staffers whose names I could retain only hours at a time. Their visits were usually to take vital sign readings, administer drugs, or change IV bags. More often than not the nurses and technicians were of Filipino descent, so I got plenty of practice telling them about the screenplay I plan to write about my dad in WWII.

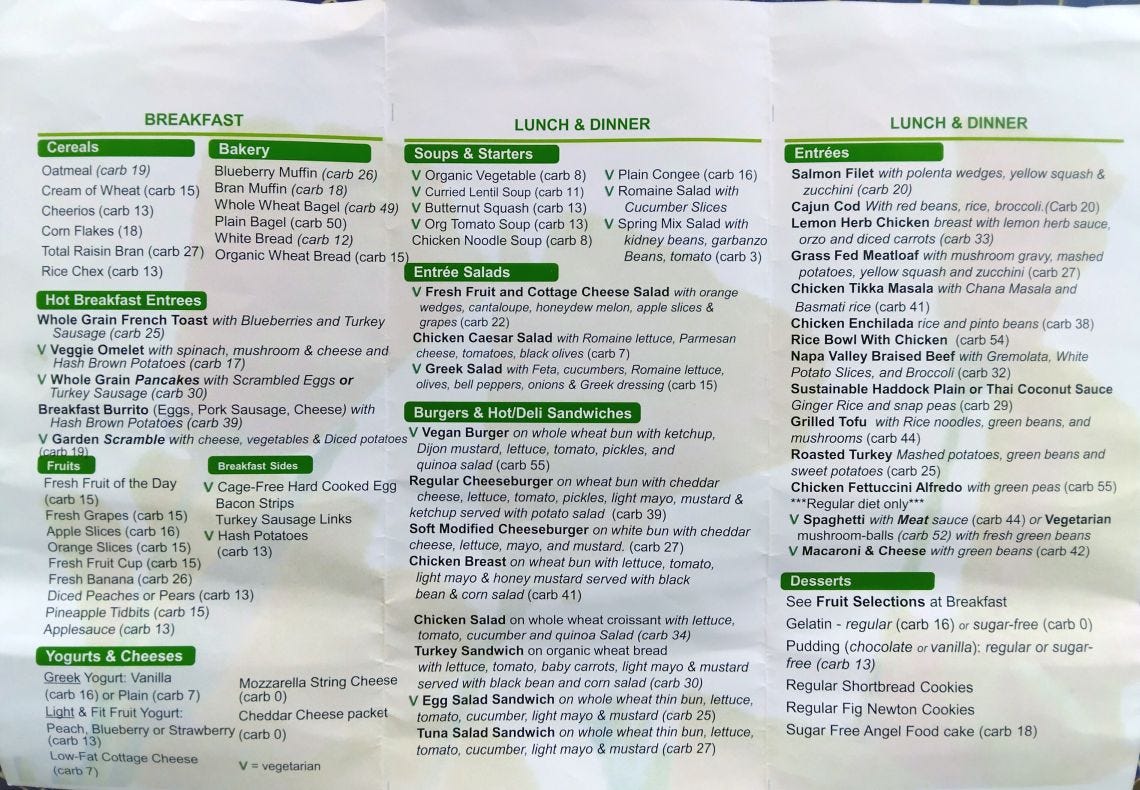

Another memorable part of being hospitalized was the cuisine. To my surprise the meals at Kaiser were mostly palatable (it helped that I had an appetite). Considering they were mass-produced and microwaved I would rank them higher than airline food, if only for the larger portions. And you won’t find airlines with menus like this every day:

Of the dinners, I’d say the Salmon Filet was consistently the best, simple yet effective. All I needed was a glass of sauvignon blanc. Alas the Chicken Tikka Masala was meh, not recommended for anyone who knows Indian food. The Napa Braised Beef (locally raised) with gremolata was their attempt at Osso Buco, which I’ll have to try at a real Italian restaurant for a fair comparison.

Considering this is Kaiser’s idea of a “heart healthy” menu, I almost have to laugh. But I was grateful whenever they didn’t hold back on the butter or half-&-half; after my operation they vanished along with the cheeseburgers.

One unique aspect of my medical adventure was the national election taking place, which I hoped would not distract the doctors and nurses at a critical moment. As it turned out, I need not have worried, for everyone stayed focused on the tasks at hand like true professionals. As I often remarked, “Life goes on.” Everyone agreed. I didn’t even watch TV, preferring my tablet with wi-fi. After all, I was supposed to keep my blood pressure down!

The Operation

Eventually the Big Day came, then was postponed, as a more urgent case came up requiring the surgeon’s immediate attention. So my operation took place on the sixth anniversary of my mother’s death (Nov. 9th). I still don’t know what to make of that sync, but there it is. The procedure required very little from me, except to show up properly scrubbed. In the early morning I was wheeled down to the surgery section to complete the formalities and get shaved in unexpected ways. Once I was in the operating room, they got down to business quickly. I had planned a little speech to thank everyone in advance, but they knocked me out before I could speak. From that moment until I awoke in yet another ICU, I was gone. Zippo. Nada.

The acronym for the procedure is CABG (“cabbage”): Coronary Artery Bypass Graft. Without going into much detail, they took pieces of artery and vein from my left arm and leg, plus a more conveniently located artery in my chest, to create detours around the three blocked arteries. During this part I was basically a cyborg, kept alive by a heart-lung machine, aka “the pump”.

Though heart surgery can now be performed “off the pump” and even through the intact ribcage, in my case the traditional method was doubtless more efficient, given how much work had to be done. My sternum was split to open the ribcage and afterwards fastened with stainless steel wires (permanent). The outer incision was sealed with medical super glue, which eventually peeled off, leaving a neat scar down the center of my chest: the mark of membership in the Triple Bypass Club.

Surprising Visions

If you were hoping to hear about profound mystical insights, for ex., in a near-death experience, sorry to disappoint you. The operation went as smoothly as anyone could have hoped, and I was out cold for the duration. However, a couple of noteworthy events took place soon after the surgery for which I still have no explanation.

I had been told earlier that after the anesthesia wore off and I regained consciousness, they would wait and observe briefly before removing my breathing tube — note that I was intubated while unconscious, and I never actually felt the tube at any time. My first memory was in a disembodied state, which in my view might as well have been a dream or hallucination. I was in pure darkness with no sensation of my body, let alone being located in a room. But I heard someone tell me they were going to remove my tube, and that I should hawk up whatever fluid was in my lungs. Even though I recall doing that (in the most abstract sense, without sensations), I have no certainty about my actions then, nor did I discuss the procedure with anyone later.

During that event the only thing that appeared in my field of vision was a browser window — yes, like the one on your computer — that had a big “X” in the middle. And on top of that were countless pop-up windows, each also containing an “X”. Once the tube came out and I was hawking up fluid, the pop-ups closed in rapid succession. It felt like a malware infection in reverse, i.e., the malware was being purged from my system — perhaps an entire timeline was being shut down and deleted. When I finally came to my senses in the ICU, my first thought was of Simulation Theory. I have never taken it literally in the sense of existing in a computer-generated Matrix. But it sure seemed to me that this was what the browser experience was pointing at.

As if that wasn’t enough, later that night (or the next day — time had become quite nebulous), I had another vision, this time while awake, with eyes open. Upon a curtain that separated me from the next patient I saw a oblong outline hovering in mid-air, morphing as if alive. More than anything else it resembled the glowing animation that runs on my tablet screen when it’s recharging. Whether or not it was a hallucination, it points again at technology, either as a metaphorical projection unique to me, or the metalevel of a shared illusion.

It’s not as though I lacked for what we usually call spiritual thoughts or feelings. I’d be amazed at anyone who could endure something like open heart surgery without talking to God at least once. However in my case I distinguish between ingrained responses and my actual cosmology, which does not require a self-existing personal deity to whom we should appeal for favors or show gratitude. We’re living in a vast mystery that cannot be fully apprehended with language. Indeed our concepts add distortions at the same time they attempt to illustrate — more on that later.

Recovery and Release

My post-op progress was for the most part a best-case scenario. While I did not keep track of the clock or calendar, for sure they had me up and walking in the ICU by the next day, closely supervised and using a walker. Those first tentative steps felt like a real triumph, and aside from fatigue and brain fog there was little genuine discomfort — that is, until later, when I suffered a spasm in my lower back, perhaps from the accumulated stress of hospitalization, triggered by sitting the wrong way while trying to eat lunch.

That stabbing pain was the most alarming event of my entire stay, since a chiropractic adjustment was out of the question, and I needed immediate relief. The only option was a muscle relaxer, which was quickly approved; there was a small risk, for I was a heart patient already under the influence of multiple meds. Fortunately the drug did its job, and with a heat pack under my back I was able to rest at last. It was humbling, for I felt utterly vulnerable and could not kid myself about my strength of will in these circumstances.

I graduated from the ICU the next day, sooner than I thought possible, after I demonstrated not only the ability to walk unassisted in the hall, but on a flight of stairs. In my building it takes two flights of stairs to reach my flat, so this ability was crucial. By this time I was quite ready for another move. The patient next door was having a paranoid episode, which only abated when his wife arrived and talked him down. It was a reminder that individuals can have radically different experiences in the same hospital, treated by the same people.

Alas, there would be no more private rooms for the remainder of my stay. I was transferred to the One North ward, for patients awaiting release. At least I had a window with a view and a large chair that I was encouraged to use when not in bed. As the days passed my medical accessories were gradually removed, which improved my mobility and morale. I used the bathroom by myself, with a certain amount of equipment in tow. At all times I carried a heart monitor, which often needed a fresh battery or a good whack (from a nurse) to keep running. In my hazy hindsight I’m amazed at how I got around, esp. with chest tubes draining into a plastic box — among the last items to be removed, along with a pair of pacemaker wires that went directly to my heart. Having those pulled out was a novel sensation.

Aside from a second flareup of back pain, again subdued by the muscle relaxer, the most noteworthy mishap of the second week resulted from taking a strong laxative, given only because I hadn’t pooped since the operation. Well, I ended up going to the loo 12 times in 24 hours. As I quipped, “I’m ready for my colonoscopy now.” The frail military-grade toilet paper provided by Kaiser only added to the inconvenience. Looking back, this part was the comedy relief.

Having roommates in this phase was by turns trying and entertaining. The nature of the ward made rapid turnover the norm. My first roommate was the most difficult, as it soon became clear he was not just suffering noisily, he had dementia as well. This made proper sleep impossible, so I requested another room. To my surprise they moved him instead — it made more sense to give him his own room, so as not to inflict the same ordeal on another patient.

The next day a new roommate was rolled in. James, a completely sane and agreeable fellow, had just been given a heart valve replacement via catheter. I didn’t know the procedure even existed until he described it. His surgery had been far less invasive than mine, so he only stayed two days. The man who took his place, David, was a colorful character, a retired DJ with rich memories of San Francisco’s music scene of the ‘60s & ‘70s. He was not a surgical patient, but had been admitted for alarming symptoms due to accidental over-medication. As local old boys with a Big Lebowski counterculture verve in common, we hit it off at once. I like to think we cheered each other up.

If you have the endurance for tales from the senior care home where I spent the next two weeks, plus my takes on the medical system and the mysteries of cardiovascular disease, I will get around to all of it soon.

Great piece Wayne, so happy you made it back in one solid piece.

Hanz

Marvelous, masterful narrative writing, subtly replete with the big messages that seriously matter, Wayne ~ the really transformative gifts are always so weighty, so unwieldy.. Feeling the sensitive nature of what you experienced even more keenly now, I can only imagine the variety of thoughts that must come and go for you since the operation. How has the wild experience changed your meditative patterns in the now, your 'vision' of -- well, 'you' -- and of the unusual journey of this particular life? With admiration and respect for a fellow artist & a 'mad' liver of life~ KF <3