“There will come a time when it isn’t, ‘They’re spying on me through my phone” anymore. Eventually it will be, “My phone is spying on me.” ~ Philip K. Dick

The distinction I make between Huxley’s “negative utopia” (described previously) and cyberpunk dystopia is that the former trope shows transhumanist society working as designed, like it or not — while the latter shows the ideology’s failure to deliver on its promise, leaving us miserably semi-calcinated in the Solve et Coagula process, unable to revert to a status quo ante save-point or to complete the transmutation.

The blame may be allocated any number of ways: blame the peasants for resisting inevitable progress; blame the politicians and oligarchs for corrupting the vision; blame human nature, which could not be modified sufficiently, etc. The cyberpunk ethos, “High Tech/Low Life” applies to our imperial decline phase, in First World urban milieus at least; it’s telling that the subgenre assumes a city-centric POV is the only one that matters.

Cyberpunk’s psychic landscape often takes on a phantasmagorical, fever-dream aspect as people slowly go mad from despair, cognitive dissonance, and toxic technologies. When humans realize they are but the soft, squishy parts of the Moloch Machine, escapism becomes a culture driver, i.e., another innovative scam for the technocratic elite (the only folks who always seem to thrive).

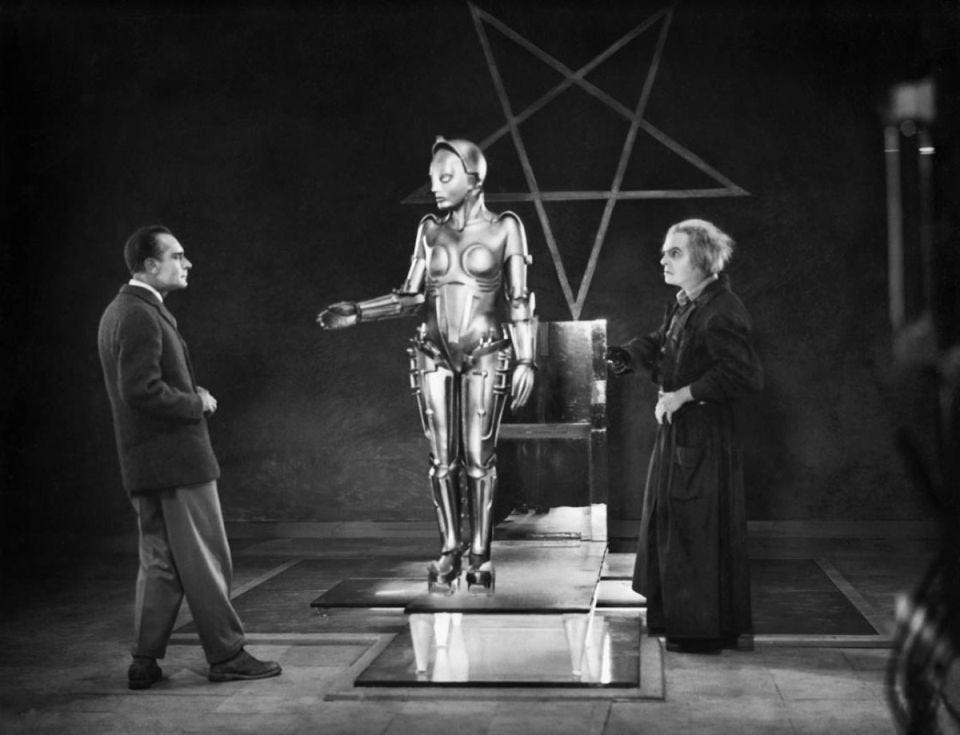

The nightmarish flipside to Wells’ techno-optimism emerged in pop sci-fi even before "Things to Come” — as “Metropolis” (1927), directed by Fritz Lang, based on the 1925 novel by his wife Thea von Harbou, who co-wrote the adaptation.

This German Expressionist epic, set in the 21st C., established now-ubiquitous sci-fi tropes: the oppressive megacity, the mad scientist, and the fembot. If that tower gives you Babel vibes, this is just the beginning.

There’s no mistaking Metropolis for an Uncanny Village: the Moloch Machine must be fed! Temps and gig workers first!

Maria, a labor activist, is kidnapped by Doctor Rotwang, who built a robot to replace his lost love Hel (yeah, robosexuality is that old). His new cray-cray idea is to give his robot Maria’s likeness, so the imposter bot can undermine the workers’ movement — at least that’s how he sells the plan to Fredersen, the oligarch master of the city. This visual motif will become very, very familiar, for a variety of purposes:

A century ago the terminology for what happens to Maria in this iconic scene did not yet exist. Now we would say she is undergoing full body and brain scans, to give the Maschinenmensch lifelike skin and behavior — techno-fetishists are still pursuing this elusive goal today. Is it really that hard to get a date?

Fredersen (left) looks nonplussed at how Doctor Rotwang spent his venture capital. Perhaps that set design is a little on-the-nose, too.

Voila! The Robo-Whore of Babylon makes her Material Girl debut, riding the Beast!

I’ve given away enough spoilers; let’s just say trouble ensues. We’ll dive deeper into robots, cyborgs, AI, and brain interfaces soon.

Dystopia would not be the viral meme we know today without George Orwell’s novel “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” published in 1949, translated into 65 languages and adapted in multiple formats: radio, film, TV, & stage, inspiring and depressing generations of writers, artists, and musicians. This retrofuture crapsack world has so penetrated the Western mind, now all you need is the adjective Orwellian.

Winston Smith in his wagie cagie at Google — sorry, the Ministry of Truth

Though 1984’s surveillance state looks dated by today’s standards, the social dynamics remain uncannily relevant. Without brain implants or genetic mods, the Tyranny Machine dribbles oil and sheds parts like an old Norton motorcycle on a bumpy road. No one has any illusions about good times just around the corner. Even the past offers no cause for hope, as it is revised constantly to support the current narrative, which can shift overnight and turn allies into enemies or vice versa. Language is redesigned as well, to curb the public’s ability to think, let alone engage in meaningful discourse.

As transhumanism gains traction in the high-tech subculture, the threat behind the promise is that if we do not press onward and bring the Brave New World to fruition with all due haste, we shall be trapped in 1984. Another interpretation: 1984 is but a transitional stage, i.e., purgatory rather than eternal damnation. The decades-long war racket of Oceania, Eurasia, & Eastasia serves as a controlled burn; yet even without a nuclear or biological holocaust, these superstates will ultimately collapse from within. These are the last vestiges of the Old Order to be dissolved in the alchemical flask. Going by the Wells/Roddenberry timeline, the next phase, flaming-trashcan anarchy, precedes the birth of Techno-Utopia. Of course that cheery scenario will depend on the timely arrival of advanced benefactors who can rekindle the Promethean fire and enlighten the remnants of humanity.

A key factor often overlooked by the social alchemists is that the deeply traumatized survivors of a civilization-ending cataclysm cannot simply be washed and fed and sent off to Tomorrowland, whether it’s beneath a dome or deep underground. Or might our wise benefactors have a new treatment to heal everyone’s trauma-based disorders? Perhaps a technique to erase painful memories and implant a new worldview to match their New World?

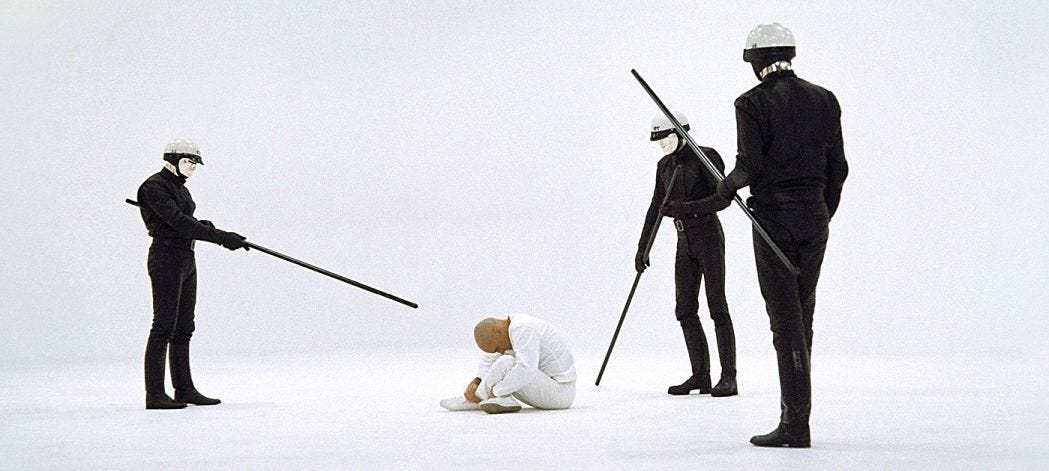

George Lucas’ 1971 feature debut “THX 1138” depicts a variation of the theme; unlike “Brave New World,” no one would mistake this tech-driven subterranean society for even an attempt at utopia. Its NPC drone citizens have no family names, no history or culture, no connection with nature or spirit, no agency beyond consumer choices, and no purpose but to be good worker ants. They seem scarcely more human than the robot cops, except for the few oddballs who step out of line. Again, the only sane option for the protagonist is to escape, even if it means venturing into the unknown.

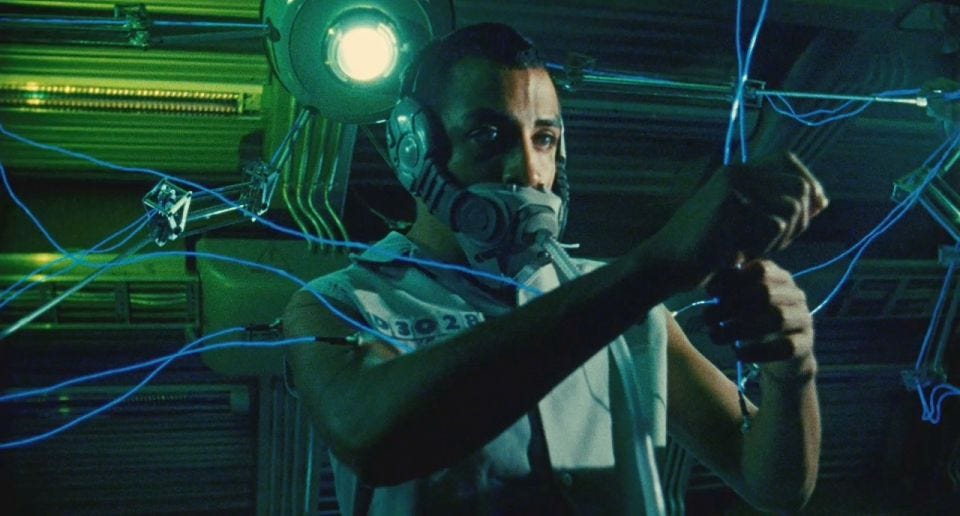

Alex Rivera’s “Sleep Dealer” (2008) presents a near-future dystopia from the POV of Memo Cruz (Luis Fernando Peña), an impoverished hacker from Oaxaca who goes to Tijuana to join the high-tech labor pool. Rather than cross the now impregnable U.S. border, they work remotely through robot bodies. Thus Americans get Mexican labor without the Mexicans. This award-winning indie film also shows love interest Luz Martínez (Leonor Varela) working another cyberpunk gig, memory trading, plus an evil corporation using drones to enforce its control over the water supply. In other words, it looks like the future next door.

“Hey, don’t knock selling memories. It pays better than OnlyFans.”

Yet another flavor of cyberpunk is served up in Steven Spielberg’s “Minority Report” (2002), based on the 1956 novella by Philip K. Dick. Despite its futuristic conveniences, there’s no question that Washington, D.C. in 2054 is straight-up dystopia. The sci-fi innovation here is the Precrime program, which uses the visions of three clairvoyants (“precogs”) to arrest and imprison would-be killers. As injustice systems go, this one works great, until it doesn’t. Here the Precrime Chief John Anderton (Tom Cruise) confronts precog Agatha Lively (Samantha Morton), with brain sensors attached to her head, because of course.

“Say, have you ever heard of Cocteau Twins?”

Perhaps the only near-future dystopia even more bleak and hopeless than “1984” is Alfonso Cuaron’s “Children of Men” (2006), based on P.D. James’ 1992 novel. Set in 2017 (just a tad early), the controlled demolition of society is driven by a worldwide loss of fertility in addition to global depression and war. Without the prospect of future generations, humanity falls into despair, fanaticism, and nihilistic savagery.

“Children of Men” goes so far into the 1984 red zone, it makes cyberpunk look like the good old days. The plot hinges on the ever-morose Theo Faron (Clive Owen) doing all he can to save Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), the only known pregnant woman left. When the film first came out, that scenario seemed so unlikely, yet it disturbed me anyway. Strange how time changes everything.

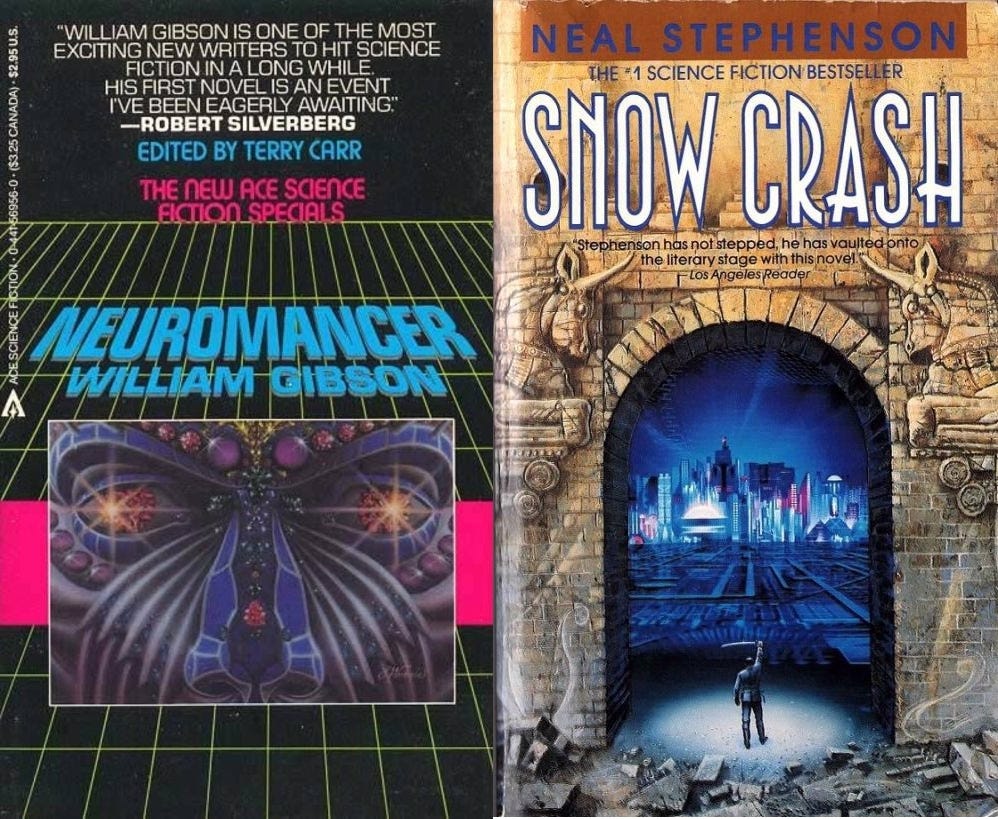

Obviously I cannot cover all the major books, let alone the films, TV, anime, & games that exemplify the High Tech/Low Life aesthetic. For me, among the genre-defining classics, two novels stand out: William Gibson’s “Neuromancer”(1984) and Neal Stephenson’s “Snow Crash”(1992). Like all futuristic visions, cyberpunk dystopia has become almost too familiar, as if it were just another trope competing with aliens, zombies, and vampires for our attention. But it’s also where we live, for now at least.

This is also just a great cyberpunk primer. Cheers.

You are a great writer!