In contrast to Wells' essentially optimistic vision of the future, after the necessary sacrifices of the Solve et Coagula process, Aldous Huxley wrote "Brave New World" (1932). Huxley's "negative utopia" spelled out the price humanity would have to pay for the materialist, technocratic heaven on earth: a caste system based on eugenics, with psychological conditioning to eliminate the traditional family, to substitute hedonism for self-realization, and to quash independent thought for the greater good: Community, Identity, Stability.

“Alphas don’t eat bugs, silly! Unless you mean lobster, hahahaha!”

"Brave New World" became the template for generations of cautionary tales, focused on the consequences of technological advances as they escalated rapidly in real life. In many such scenarios the "dark side of paradise" issue is resolved with a happy ending, which might come off as naive. Here are just a few exemplars of the subgenre:

Patrick McGoohan's TV series, "The Prisoner" lasted just one season (1967-1968), yet made an indelible mark in sci-fi history. With its disarmingly quaint panopticon community, The Village, and its protagonist Number Six stubbornly defying every attempt to break his will, the series displayed the surreal terrors and fatal flaws of the technocratic hive society, i.e., the Global Village now under construction.

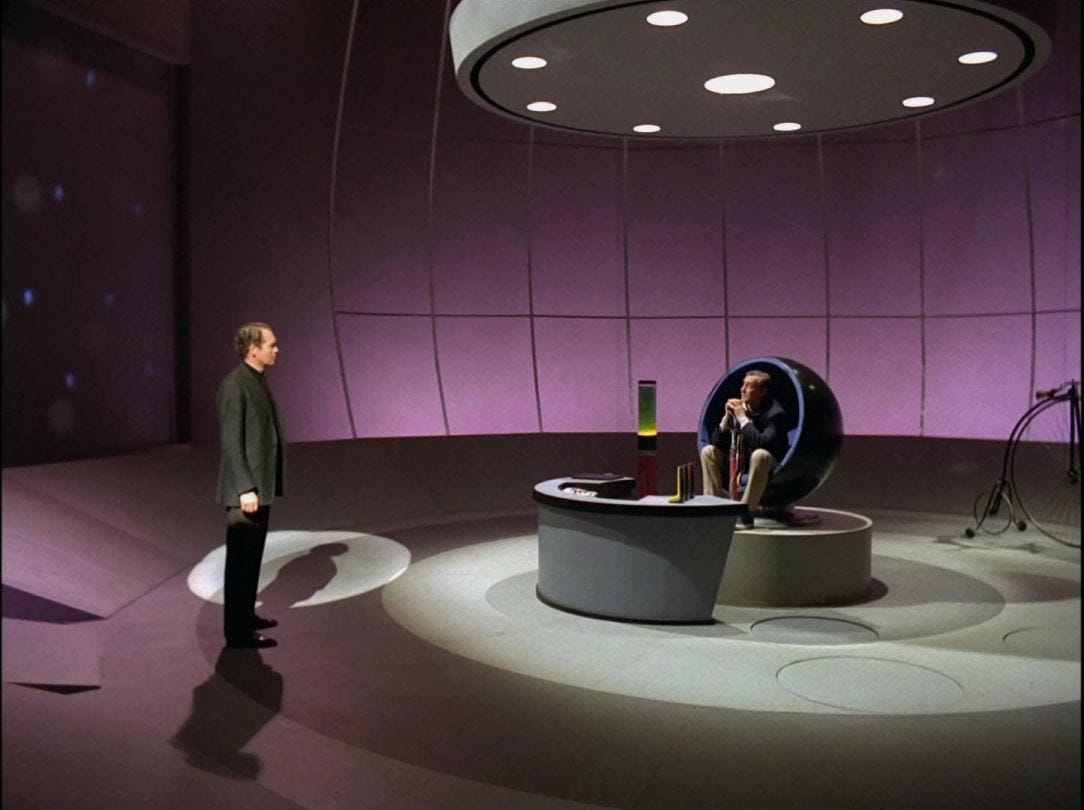

Number Six goes full-Karen and demands to see the manager.

Number Two, the Village’s chief administrator, has dealt with tough customers before. Number Six needs to accept his new reality and learn to cooperate. After all, he'll be spending the rest of his life here. The sticking point of their conflict, repeated in the intro of every episode, seems even more timely now:

Number Two: We want information... Information... INFORMATION!

Number Six: You won't get it!

Number Two: By hook or by crook, we will.

Luckily the Village's HMO covers a wide range of attitude adjustment options. If Number Six has to be the nail that sticks out, they have state-of-the-art hammers.

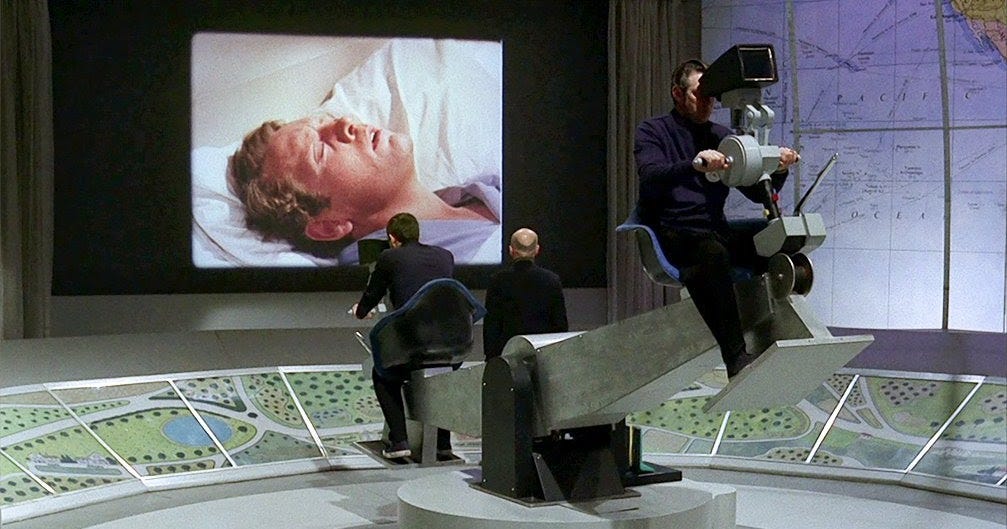

The Control Room keeps an eye on the recuperating Number Six. The Village is all about security and comfort: escape-proof and revolution-proof from top to bottom. They even hold elections; in the “Free For All” episode, Number Six is persuaded to run for office. This is a must-see series, and it’s free to watch on YouTube (for now).

The Prisoner, Episode 1: "Arrival"

“Logan’s Run” (1976, Director: Michael Anderson)

This City of Tomorrow ticks all the post-apocalyptic boxes, including the Domed City trope that highlights the theme-park society’s need to isolate itself from the reality outside its sphere of control. The citizens enjoy easy, vacuous lives, with AI-assisted booty calls, but there's a catch. It has to do with keeping the population down.

Jessica 6 realizes she’s dealing with a Sigma rather than an Alpha. Bloody algorithms!

A common trope of this subgenre is that the hero’s journey is an escape adventure. Logan 5 (Michael York) and Jessica 6 (Jenny Agutter) must find a way out of their high-tech Plato’s Cave to reach the Real World. Similarly, the whole arc of “The Prisoner” follows Number Six’s attempts to escape The Village, whose complacent citizens behave like scripted NPCs in a video game.

“Tomorrowland” (2015, Director: Brad Bird; Writers: Damon Lindelof & Brad Bird)

Disney's "Tomorrowland" catapults the utopian narrative into another reality, i.e., the gleaming Futuropolis already exists in an adjacent dimension, thanks to Plus Ultra, a secret society of visionary geniuses founded in 1889 by Jules Verne, Gustave Eiffel, Thomas Edison, and Nikola Tesla (quite a stretch, those last two). Later members included H.G. Wells, Mark Twain, Amelia Earhart, Ray Bradbury, and Walt Disney. Their motto: Cras Es Noster (Tomorrow Is Ours).

Even fans of the "Revelation of the Method" may be amazed at the level of disclosure propaganda masked as family entertainment: "Tomorrowland" is the Disneyfication of Breakaway Civilization theory. In this version, the Plus Ultra elitists hoarded the most revolutionary scientific achievements in their private utopia, saving them up for whenever we’re ready (in their judgment).

The film's ideological conflict is represented by the Plus Ultra dropout Frank Walker vs. Tomorrowland's governor David Nix. Whatever one thinks of Wells-style futurism, Nix (Hugh Laurie) is technocracy incarnate, warts and all. Sci-fi writers should note that he did try to warn humanity of the Impending Catastrophe (climate change, for starters) but realized that instead of changing course, we kept on heading for the cliff, as if cautionary tales were only self-fulfilling prophecies. It makes me think about the power of the imagination and the need for writers to visualize better alternatives than the transhumanist agenda.

One unquestioned assumption of the film is that humanity's collision course with disaster is due to a lack of technical solutions, rather than the Psychos in Charge who made civilization this way on purpose, to serve what some call a Luciferian vision, in which we’re just cogs in the machine — except for those rare geniuses who need to be recognized early, groomed, and elevated to proper positions of mastery.

The trope parade cannot help but include super-androids like pixie dreamgirl Athena (Raffey Cassidy), who recruited young Frank (Thomas Robinson) at the 1964 New York World's Fair. This leads to a squicky moment later, when midlife-crisis Frank (George Clooney) reveals he still has feelings for Athena, who hasn't aged a day. Eww, Disney.

Despite creative guerilla marketing, for ex., The Optimist, an alternate reality game, and tantalizing clues leaked by the whistleblowers of Stop Plus Ultra -- the film was a box-office flop, losing Disney over $100 million (just business as usual nowadays). It's actually sad in a way, given how rarely Hollywood invests so much in original stories. Even with its obvious flaws, “Tomorrowland” is significant in its own way, like Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda films. I would only recommend watching it for free. If you see the ending, you may be relieved that this film hasn’t become more influential.

Disney's ARG Marketing of "Tomorrowland"